Improvements to Uptime Monitoring

Improving our Uptime Monitoring Tool

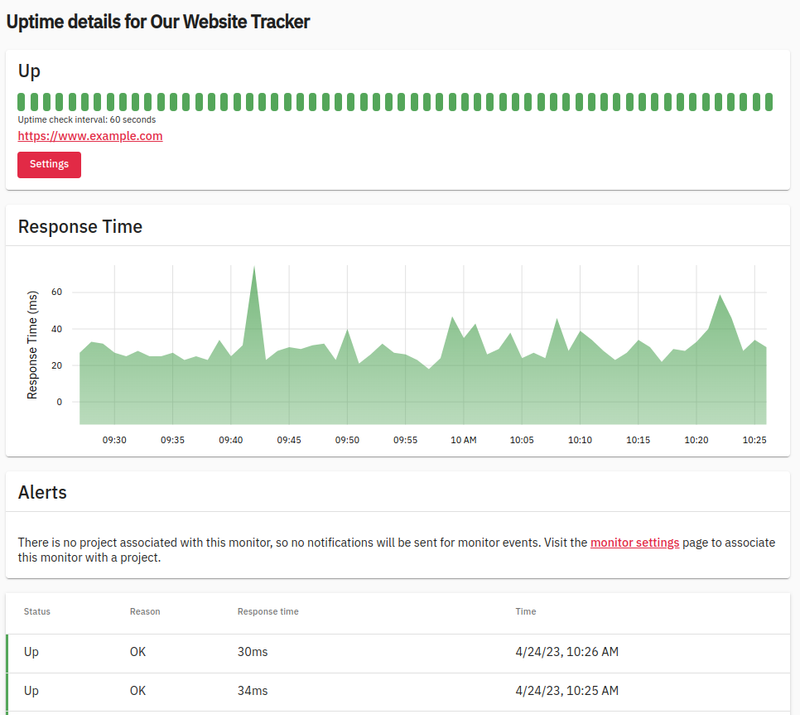

We wanted GlitchTip’s uptime monitoring feature to support more configuration options around timeouts and check intervals, while providing excellent performance for both small and large instances.

Goals

- Fast and batched queries – we want to ensure PostgreSQL is used as efficiently as possible. We need to batch both database reads and especially writes.

- Allow to-the-second precision on timeout and check intervals. If you want your site checked exactly every 62 seconds – we should do that. If you want it checked every 1 second with 60 second timeouts, we need to support that, too.

Tracking monitor state

In prior versions of GlitchTip, we would check for the previous uptime “check” to determine if we need to run another. If the interval was 60 seconds and the last check was >= 60 seconds ago, it would run another check. This solution is simple but limited. It can’t support timeout values that are higher than intervals without saving the state of a started check. Saving state means PostgreSQL writes, which we want as few of as possible. Joining the monitor and monitor check tables also carries a minor performance penalty.

We came up with a more stateless solution. We count seconds using redis’s INCR from an arbitrary start time. Then apply some math with modulus division to determine when exactly each monitor needs to perform it’s check.

- If the monitor interval is every second, then any number divided by 1 will have a remainder of 0. Therefore it will always run the check.

- If the monitor interval is every 30 seconds, then only the 30, 60, 90, etc second “tick” will have a remainder of 0.

Now we know when to run the monitor check and we can ignore prior checks entirely. To further optimize this, we batch database reads. Every 10 seconds, a celery task runs to read our monitors table for any monitors that need to run in the next 10 seconds. The value of 10 is arbitrary.

monitors = Monitor.objects.annotate(

mod=tick % Epoch(F("interval"))).filter(mod__lt=UPTIME_CHECK_INTERVAL

)

Notice the modulus value only needs to be less than our check interval. This query is fetching any monitor that needs to run in the next 10 seconds. It sounds too simple to work. Thanks, math! The query is very quick even with thousands of monitors. If someday we have millions, we would need to split this query up.

Next we batch our monitors based on when they need to run. If the interval is 2 seconds, then we need to place that monitor in a group that runs every other second. Here’s a snippet to filter them that also groups the timeout into fast and slow groups.

fast_tick_monitors = [

monitor

for monitor in monitors

if i % monitor.interval.seconds == 0 and monitor.int_timeout < 30

]

Now we have batches of uptime monitors based on the next 10 seconds and whether they might be slow or not. We will utilize celery’s ETA feature to set when they need to run. We’ll also expire them after a minute just in case celery gets backed up.

perform_checks.apply_async(

args=([m.pk for m in monitors_to_dispatch], run_time),

eta=run_time,

expires=run_time + timedelta(minutes=1),

)

perform_checks accepts a list of monitor ids. This function uses Python’s asyncio and aiohttp to make all of it’s checks concurrently.

results = await asyncio.gather(

*[fetch(session, monitor) for monitor in monitors], return_exceptions=True

)

It gathers all results and later bulk inserts them into PostgreSQL. This bulk insert is the reason we grouped them by timeout, as a slow responding check will take some time to finish running.